肺癌筛查的挑战:已实施项目综述

引言

肺癌是全球最常见的导致癌症相关性死亡的原因,吸烟是肺癌最常见的危险因素[1]。尽管吸烟人群比例在过去几十年中有所下降,仍有37%的美国成年人正在或曾经吸烟[2]。尽管吸烟人群肺癌罹患风险增加已是人尽皆知,但肺癌在诊断时多已处于晚期,5年生存率低至15%[3-5]。20世纪70年代初,美国国家癌症研究所赞助了多项大规模研究以评估使用胸部X线片和痰细胞学检查进行肺癌筛查的效果,但是这些研究未能证明死亡率有任何降低[6,7]。

2011年,美国国家肺癌筛查试验(National Lung Screening Trial,NLST),一项多中心随机对照试验,明确了每年低剂量胸部计算机断层扫描(Low dose chest computed tomography,LDCT)进行肺癌筛查可以使肺癌高危人群的相对死亡率降低20%[8]。此外,NLST报告证明全因死亡率降低6.7%,是所有癌症筛查方式中最高的[8,9]。为防止一例肺癌死亡,需要进行LDCT筛查的人数为320[10]。相比之下,预防一例乳腺癌或结肠癌死亡所需的筛查人数分别为1904和1250[11,12]。

鉴于这一证据,美国预防服务工作组于2013年建议使用NLST标准对肺癌高危人群进行筛查,并将年龄上限扩大到80岁[13]。包括国家综合癌症网络、美国胸外科协会和美国胸科协会在内的数个权威机构都发布了类似的指南[14,15]。2015年,医疗保险和医疗补助服务开始覆盖LDCT肺癌筛查,但参与者需满足接受戒烟咨询和参与国家登记等多项要求。最近公布的NELSON试验(荷兰-比利时肺癌筛查试验)再次肯定了肺癌筛查获益并为上述指南提供了进一步支撑,其结果显示10年随访期内男性和女性的死亡率分别降低了24%和33%[16]。

尽管肺癌筛查对高危患者的获益令人信服,但在美国只有3.9%符合条件的患者成功地被纳入筛查计划[17]。一些研究小组使用轶事、回顾性和混合方法的数据来确定肺癌筛查实施中的障碍[18]。一般来说,肺癌筛查项目尚未尚未取得与基于人群的乳腺癌、宫颈癌和结肠直肠癌的成本效益筛查项目相同的成功[19]。本综述概述了肺癌筛查当前面临的挑战,总结了有效筛查的原则,并详细介绍了几个肺癌筛查项目在多种医疗环境中的实施经验。

肺癌筛查面临的挑战

尽管强有力的证据支持每年对高危患者进行LDCT扫描,但这一筛查项目的参与率却大相径庭[17]。由于肺癌筛查策略的复杂性,其实施中的潜在障碍是多方面的。这些挑战可分为患者、医务人员和筛查系统的问题[20]。

患者通常不知晓肺癌筛查策略,或者由于担心确诊癌症及成本问题而拒绝接受筛查。Simmons等人通过半结构化访谈发现,大量肺癌高风险人群从未听说过LDCT,也没有医务人员向他们普及肺癌筛查概念[21]。参与者还注意到对确诊癌症的恐惧以及对肺癌筛查成本和保险覆盖的担忧。最近一项针对不同类型和低收入门诊患者中肺癌高风险人群的定性调查分析印证了这些发现[22]。被调查者对肺癌筛查的目的了解不足,希望获得关于筛查收益和危害的个体化信息。

肺癌筛查的独特之处在于其筛查对象是长期大量吸烟人群,这与主要基于年龄的结肠癌和乳腺癌筛查不同。长期大量吸烟相关的羞耻感可能导致肺癌筛查参与度下降[23,24]。此外,高风险吸烟行为常见于较低的社会经济阶层[25]。这些人的财政和交通资源较少,很少有机会休假,在预防保健和肺癌筛查方面获取的社会支持也较少[26]。

基层医生是解决预防保健措施和识别肺癌筛查人群的一线工作者。然而,基层医生层面的已知障碍包括对肺癌筛查指征的了解有限,以及与患者讨论肺癌筛查流程的时间有限[21]。此外,鉴于NLST的高假阳性率,仍有部分基层医师对肺癌筛查的益处表示怀疑[27]。基层医师还缺乏诸如美国家庭医生协会等国家组织的担保[28]。美国家庭医生协会指出根据年龄和吸烟史推荐或反对高风险人群进行LDCT肺癌筛查的证据并不充分[29]。肺癌筛查策略的拥护者尝试通过提供有重点的外展服务和教育以提高基层医生的肺癌筛查意识,但这一尝试的效果尚不清楚[30,31]。

肺癌筛查系统建设需要强大的医疗设施来无缝衔接多个专业和辅助资源。如前所述,这可能需要综合性的癌症中心或实施健全的转诊政策,并建立密切沟通的医疗服务网络以随访和处置阳性结果。此外,肺癌筛查是资源密集型项目,需要大量辅助人员和设备。例如,CT扫描仪的数量会影响医疗系统的可扩展性及其有效筛查患者的能力[20]。还需注意的是,肺癌筛查策略的保险范围需要美国放射学会CT认证。肺癌筛查项目必须通过多个评估领域认证,包括人员资格、质量控制/质量保证和图像质量[32]。此外,认证还要使用美国放射学会肺部CT筛查报告和数据系统(Lung-RADS)或类似的结构化报告和管理系统。肺癌筛查项目应为患者和转诊工作者提供保证及标准化程序以实现高质量的筛查及获取适当的后续治疗[33]。

此外,一些卫生系统的挑战源于卫生政策的差异。例如,肺癌筛查策略由于不被国家卫生绩效指标所认可,通常不被卫生系统优先考虑。美国医疗保险和医疗补助服务机构实施了基于绩效的激励支付系统计划,根据各种质量措施的绩效对卫生系统进行补偿[34]。作为该计划预防保健倡议的一个组成部分,结肠癌、乳腺癌和宫颈癌的筛查率被纳入卫生系统绩效中。然而,肺癌筛查尚未被认定为预防保健措施。这阻碍了卫生系统将肺癌筛查策略作为癌症筛查项目的高度优选项。

理想的肺癌筛查策略

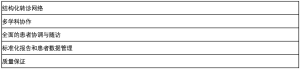

一些工作小组通过从核心到关键要素的各种描述,提供了高质量肺癌筛查的观点和专家意见[20,31,35-38]。美国胸科医师学会(American College of Chest Physicians,AACP)和美国胸科学会(American Thoracic Society, ATS)的胸科肿瘤学会议利用已发布政策声明中的循证审查和专家意见,确定了有效肺癌筛查策略的几个核心组成部分[35]。共同要素包括结构化转诊网络、多学科协作、全面的患者协调和随访、标准化报告和数据管理系统以及质量保证措施的实施(表1)。

Full table

强大的转诊网络对肺癌筛查项目的可行性至关重要。肺癌筛查的指征确认主要依赖于基层医生,这是患者预防保健的一部分。因此,理想的肺癌筛查项目有赖于基层卫生服务系统的强大投资,并提供政策和后勤支持以保证基层医生的有效转诊[31]。已经有一些面向基层医生的教育资源可以促进其遵守国家筛查准则。关于肺癌筛查收益、保险报销指导和共享决策过程的基层医生教育的增加可能会提升肺癌筛查项目的转诊量[30]。

多学科参与是肺癌筛查策略成功的必要条件[38]。这通常需要基层医师、呼吸内科、肿瘤内科、胸外科、放射学、病理学、戒烟顾问和护士协调员的参与。这些机构的代表通常会定期召开肿瘤委员会会议或肺结节会议。鉴于多学科合作在实施有效筛查中的重要性,综合性的肺癌筛查中心会提供在单一场所内为特定患者传递决策共享、影像评估、解释和管理的机会[30]。为患者提供“一站式服务”以便于肺癌筛查项目实施。需要注意的是,创建和维持这样一个肺癌筛查中心需要大量的资源和基础设施。

由于胸部手术固有的侵入性,在LDCT筛查发现肺结节的治疗中,专科医生通常是最后咨询和参与指导的。然而,胸外科医师对LDCT阳性结果的专业知识和处理可以优化患者管理,因而有必要尽早介入[5]。此外,多学科团队研究和处理LDCT发现的肺结节可以避免过度及不必要的诊断资源和介入手段使用[39]。例如,高度怀疑肺癌的肺结节患者可能更适合诊断性楔形切除后接受肺叶切除术,而不是可能出现假阴性结果的经皮活检术。

在患者协调和随访方面,患者引导员(通常是具有中等水平的放射科、内科、呼吸科或外科医生)对项目的成功至关重要[31,40]。他们负责确保转诊医师遵守影像报告所述的建议,协助患者转诊至临床管理团队的相应专业医师,并协调阴性结果的年度随访。

标准化报告系统是肺癌筛查策略有效性的重要组成部分。LDCT的影像报告应传达相关的阳性和阴性结果,并包含后续处理程序[35]。最常用的结构化报告系统是美国放射学会肺CT筛查报告和数据系统。肺癌筛查计划内至少90%的LDCT扫描,应使用结构化的系统报告以最大限度地减少结节管理中的变量,并提供一致和统一的处置措施[35,41]。

最后,一个健全的质量改进计划不仅是医疗保险和医疗补助服务机构的要求,也是确保筛查计划可靠性和有效性的必要元素。ATS/AACP建议监督机构每年审查肺癌筛查计划的筛查数据和上述要素实践情况,以判定合规水平并发现相关漏洞[35]。筛查数据应包括检测结果(并发症和癌症诊断数量)、肿瘤特征和治疗模式[35]。此外,作为一项质控指标,至少90%的筛查个体应符合美国预防医学工作组的资格要求[35]。

实施肺癌筛查经验总结

近年来,一些机构在多种医疗系统和社会经济环境中建立了肺癌筛查项目。已公布的研究成果为后续肺癌筛查项目提供了宝贵的信息,包括成功要素、挑战和可以规避的陷阱。许多项目重申了上述ATS/AACP提出的政策和建议。所选研究的概述见表2。

Full table

从退伍军人事务部到社区和学术机构,患者和医务人员对肺癌筛查策略了解不足是多个项目在多种环境中遇到的挑战[32,42,44,48,49]。Batlle及其同事鼓励新的肺癌筛查项目投资战略营销活动,以提高公众对其存在和固有收益的认知[32]。推荐的高成本效益项目包括大型巡诊、患者教育研讨会、社交媒体推广以及当地医生经验的专人访谈。后者有助于在基层医生中建立强大的医师转诊网络。上述肺癌筛查计划中,三分之一的参与者是通过非医生渠道加入肺癌筛查的,这包括报纸、杂志广告、广播广告、社交媒体和口头相传[32]。Simmerman等人开展了癌症社区意识和获取研究教育计划,向少数民族和弱势群体宣传肺癌筛查概念[45]。除了对患者的指导,提供继续医疗教育也是至关重要的。既往的定性研究指出了肺癌筛查指南和报销相关知识的缺陷[50]。最近建立的社区肺癌筛查项目中发现,22.4%(80/357)的转诊筛查患者不符合国家综合癌症网络和美国预防服务工作组指南要求[43]。类似的发现也反映在学术卫生系统实施的肺癌筛查项目中[44,49]。

对LDCT阳性患者的协调诊治是另一个常见的挑战[32,44,47]。一些项目鼓励的解决方案包括雇佣引导护士和高级执业护士,指引患者到适当的临床医生和影像学机构就诊,以确保患者每年接受适当的随访筛查[32,46,48]。护士引导员是专业肺癌筛查项目的基础,负责病人咨询、整理临床结果、并协调医患沟通[51]。有一个成功的肺癌筛查项目为协调员提供了一个免费的电话号码用于解答患者询问[49]。除了高级护士的协调优势外,还可能还会带来经济效益。Gilbert和同事研究了护士指导肺癌筛查计划的经济影响,发现胸部手术和介入肺科收入的增加主要来自确诊新发疾病以及随后的评估、检查和手术[52]。

多学科参与领导肺癌筛查是必不可少的,几个已实施的研究项目都强调了这一点[32,47,53,54]。领导责任包括开发一个自我维持的基础设施,制定相应的协议,以减少患者管理中的变量。在退伍军人医疗系统内,对几个肺癌筛查入组点的审查显示,在患者选择和使用质量审核方面存在不一致[55]。在一个由多个医疗中心组成的机构内实施肺癌筛查项目的复杂性主要归因于医疗实践的内在差异。在这种情况下,项目领导必须在每个入组点指派责任医师以传达和执行有关患者选择、医生转诊、影像协议、共享决策、戒烟服务和LDCT阳性结果管理的政策[46]。此外,肺癌筛查工作量的增加自然会加重人员负担和资源消耗[46,48]。任何项目中的肺癌筛查工作量都会逐渐增加,这要求领导团队必须管理资源分配并在需要时引入资源。

据了解,吸烟率在少数民族和社会经济弱势群体中较高[56]。一个负责和有效的肺癌筛查项目将分配资源来帮助这一弱势群体。Guichet等人报告了他们针对弱势群体的经验,揭示了社会经济负担是患者遵守建议和向专家转诊的障碍[9]。肺癌筛查项目应侧重于为这些人提供社区外展服务和社会服务,以提高其肺癌筛查意识,并澄清普遍存在的肺癌筛查负担很高的错误观念[21,45]。

肺癌筛查展望

科技在患者管理中无处不在,采用电子工具来辅助医生决策是一个重大进步[43]。Ahmed及其同事介绍了一种电子调查问卷的使用情况,该调查问卷必须由希望使用LDCT实施肺癌筛查的医务人员填写以保证筛查合理性[47]。另一些人则加入了电子化的临床提醒,以便医生了解患者当前或近期的吸烟情况[57]。然而,在电子医疗记录中获取详细的吸烟史(包年和戒烟后的年数)以助力肺癌筛查仍然存在挑战[46]。毫无疑问,电子辅助设备具有创新性和良好应用前景,但我们对其可行性、可扩展性和有效性知之甚少。

改善肺癌筛查策略的另一个途径是扩展转诊平台。目前,肺癌筛查高危人群的资格确定取决于基层医生。一个有趣的理念是将肺癌筛查招募责任扩展到基层卫生服务以外的专业,急诊科已成为实施预防性医疗服务的重要社区资源[58]。急诊科患者吸烟率远远超过全国平均水平,高达48%[59]。因此,急诊科似乎是一个招募高危吸烟者使之从LDCT肺癌筛查中获益的理想平台。此外,利用急诊科招募肺癌筛查人群的优势在于大量社会经济弱势群体、少数族裔在急诊科就诊[60]。在这种情况下,急诊科往往是他们参与医疗系统互动的唯一场所。因此急诊科长期以来被认为是评估患者吸烟状况、提供简短戒烟建议、并向患者推荐戒烟计划的重要公共卫生平台[58,59]。然而,我们对急诊科识别和转诊符合肺癌筛查条件患者的能力认知有限[61]。

结论

尽管强有力的证据支持对肺癌高危人群进行LDCT筛查,但肺癌筛查的参与率同其他肿瘤筛查仍存在差距。毫无疑问,患者、医务工作者和医疗系统都面临着各种各样的挑战。然而,这些困难大多可以通过医务人员和医疗系统领导层的共同努力来克服。根据医疗系统和资源配置的差别,实施肺癌筛查项目时必须对特殊因素加以考虑。这一综述概述了一般的核心原则。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ccts-20-47). MR reports personal fees from Intuitive Surgical outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. No patients were directly involved in this review, accordingly informed consent was not needed.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:7-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Humphrey LL, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a systematic review to update the US Preventive services task force recommendation. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:411-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JJ, Cardarella S, Lydon CA, et al. Five-year survival in EGFR-mutant metastatic lung adenocarcinoma treated with EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:556-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janssen-Heijnen ML, Coebergh JWW. Trends in incidence and prognosis of the histological subtypes of lung cancer in North America, Australia, New Zealand and Europe. Lung Cancer 2001;31:123-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grondin SC, Edwards JP, Rocco G. Surgeons and lung cancer screening: rules of engagement. Thorac Surg Clin 2015;25:175-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fontana RS, Sanderson DR, Woolner LB, et al. Lung cancer screening: the Mayo program. J Occup Med 1986;28:746-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tockman MS. Survival and mortality from lung cancer in a screened population: the Johns Hopkins study. Chest 1986;89:324S-5S. [Crossref]

- Team NLSTR. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guichet PL, Liu BY, Desai B, et al. Preliminary results of lung cancer screening in a socioeconomically disadvantaged population. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2018;210:489-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goulart BH, Bensink ME, Mummy DG, et al. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography: costs, national expenditures, and cost-effectiveness. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012;10:267-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warner E. Breast-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1025-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richardson A. Screening and the number needed to treat. J Med Screen 2001;8:125-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moyer VA. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:330-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wood DE. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines for lung cancer screening. Thorac Surg Clin 2015;25:185-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berg AO, Allan JD, Frame P, et al. Lung cancer screening: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:738. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med 2020;382:503-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jemal A, Fedewa SA. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in the United States—2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1278-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali N, Lifford KJ, Carter B, et al. Barriers to uptake among high-risk individuals declining participation in lung cancer screening: a mixed methods analysis of the UK Lung Cancer Screening (UKLS) trial. BMJ open 2015;5:e008254. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mandal R, Basu P. Cancer screening and early diagnosis in low and middle income countries: Current situation and future perspectives. Krebsvorsorge und Früherkennung in Ländern mit niedrigem und mittlerem Einkommen: Aktuelles Szenario und Zukunftsperspektiven. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2018;61:1505-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carter-Harris L, Gould MK. Multilevel barriers to the successful implementation of lung cancer screening: why does it have to be so hard? Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14:1261-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simmons VN, Gray JE, Schabath MB, et al. High-risk community and primary care providers knowledge about and barriers to low-dose computed topography lung cancer screening. Lung Cancer 2017;106:42-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crothers K, Kross EK, Reisch LM, et al. Patients’ attitudes regarding lung cancer screening and decision aids. A survey and focus group study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:1992-2001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carter‐Harris L. Lung cancer stigma as a barrier to medical help‐seeking behavior: Practice implications. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2015;27:240-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carter‐Harris L, Ceppa DP, Hanna N, et al. Lung cancer screening: what do long‐term smokers know and believe? Health Expect 2017;20:59-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harwood GA, Salsberry P, Ferketich AK, et al. Cigarette smoking, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial factors: examining a conceptual framework. Public Health Nurs 2007;24:361-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katz SJ, Hofer TP. Socioeconomic disparities in preventive care persist despite universal coverage: breast and cervical cancer screening in Ontario and the United States. JAMA 1994;272:530-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoffman RM, Sussman AL, Getrich CM, et al. Attitudes and Beliefs of Primary Care Providers in New Mexico About Lung Cancer Screening Using Low-Dose Computed Tomography Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:E108. [published correction appears in Prev Chronic Dis. 2019 Nov 07;16:E149]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tong BC. Lung cancer screening: No more excuses. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155:369-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Physicians AAoF. Clinical preventative service recommendation: Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/lung-cancer.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Jokerst C, Oliva I, Mohammed TL. Clearing the air: steps for lung cancer screening success. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2015;44:113-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fintelmann FJ, Bernheim A, Digumarthy SR, et al. The 10 pillars of lung cancer screening: rationale and logistics of a lung cancer screening program. Radiographics 2015;35:1893-908. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Batlle JC, Maroules CD, Latif MA, et al. A five-step strategy for building an LDCT lung cancer screening program. Appl Radiol 2018;47:12-8.

- Kazerooni EA, Armstrong MR, Amorosa JK, et al. ACR CT accreditation program and the lung cancer screening program designation. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:38-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Services DoHH. Quality Payment Program. Available online: https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview. Accessed February 24, 2020.

- Mazzone P, Powell CA, Arenberg D, et al. Components necessary for high-quality lung cancer screening: American College of Chest Physicians and American Thoracic Society policy statement. Chest 2015;147:295-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tanoue LT, Tanner NT, Gould MK, et al. Lung cancer screening. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:19-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pedersen JH, Ashraf H. Implementation and organization of lung cancer screening. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:152. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramsey SD, Malin JL, Goulart B, et al. Implementing lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography: recommendations from an expert panel. J Oncol Pract 2015;11:e44-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goulart BH. The value of lung cancer CT screening: it is all about implementation. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2015;35:e426-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McKee BJ, McKee AB, Kitts AB, et al. Low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer in a clinical setting: essential elements of a screening program. J Thorac Imaging 2015;30:115-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin MD, Kanne JP, Broderick LS, et al. Lung-RADS: pushing the limits. Radiographics 2017;37:1975-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okereke IC, Bates MF, Jankowich MD, et al. Effects of implementation of lung cancer screening at one veterans affairs medical center. Chest 2016;150:1023-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller AT, Kruger P, Conner K, et al. Initial outcomes of a lung cancer screening program in an integrated community health system. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:733-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lanni TB, Stevens C, Farah M, et al. Early Results From the Implementation of a Lung Cancer Screening Program. Am J Clin Oncol 2018;41:218-22. [PubMed]

- Simmerman E, Thomson N, Dillard T, et al. Free Lung Cancer Screening Trends Toward a Twofold Increase in Lung Cancer Prevalence in the Underserved Southeastern United States. South Med J 2017;110:188-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. Implementation of lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:399-406. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed A, Verma N, Barreto I, et al. Low-dose Lung Cancer Screening at an Academic Medical Center: Initial Experience and Dose Reduction Strategies. Academic Radiology 2018;25:1025-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel S, Cho A, Lamont A, et al. Implementing a community hospital lung cancer screening program: a multidisciplinary program and a standardized reporting system. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:R14-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McKee BJ, McKee AB, Flacke S, et al. Initial experience with a free, high-volume, low-dose CT lung cancer screening program. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:586-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ersek JL, Eberth JM, McDonnell KK, et al. Knowledge of, attitudes toward, and use of low‐dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening among family physicians. Cancer 2016;122:2324-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Korst RJ. Systematic approach to the management of the newly found nodule on screening computed tomography: role of dedicated pulmonary nodule clinics. Thorac Surg Clin 2013;23:141-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilbert CR, Ely R, Fathi JT, et al. The economic impact of a nurse practitioner–directed lung cancer screening, incidental pulmonary nodule, and tobacco-cessation clinic. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155:416-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillaspie EA, Allen MS. Computed tomographic screening for lung cancer: the Mayo Clinic experience. Thorac Surg Clin 2015;25:121-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Milch H, Kaminetzky M, Pak P, et al. Computed tomography screening for lung cancer: preliminary results in a diverse urban population. J Thorac Imaging 2015;30:157-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gesthalter YB, Koppelman E, Bolton R, et al. Evaluations of Implementation at Early-Adopting Lung Cancer Screening Programs: Lessons Learned. Chest 2017;152:70-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, et al. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1248:107-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fung CH, Woods JN, Asch SM, et al. Variation in implementation and use of computerized clinical reminders in an integrated healthcare system. Am J Manag Care 2004;10:878-85. [PubMed]

- Bernstein SL, Becker BM. Preventive care in the emergency department: diagnosis and management of smoking and smoking‐related illness in the emergency department: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:720-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bernstein SL, Boudreaux ED, Cydulka RK, et al. Tobacco control interventions in the emergency department: a joint statement of emergency medicine organizations. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:e417-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kocher KE, Nallamothu BK, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Emergency department visits after surgery are common for Medicare patients, suggesting opportunities to improve care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1600-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cunningham RM, Bernstein SL, Walton M, et al. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs: future directions for screening and intervention in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:1078-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

王培宇

住院医师,北京大学人民医院2020级科研型博士研究生。硕士阶段师从李印教授从事食管癌患者围术期营养及加速康复相关研究,博士阶段师从王俊院士从事肺癌发病机制及肺癌诊疗的基础与临床研究。目前以第一作者发表SCI论文6篇,总IF为21.4。于 “2019中华医学会胸心血管外科青年医师论坛” 以第一作者作会议发言一次。于2019、2020全国胸心血管外科学术会议及2021食管疾病世界大会(ISDE)多次做壁报交流。(更新时间:2021/10/26)

张少伟

男,联勤保障部队第九八九医院心胸外科主治医师,解放军医学院外科学硕士,临床工作10余年,擅长胸腔镜下常规肺癌、胸腺瘤及食管癌根治手术,发表论文多篇,其中SCI论著一篇,申请实用新型专利1项。(更新时间:2021/10/26)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Patel DC, Ramsey M, Phadke A, Lui NS. Challenges in lung cancer screening: a review of implemented programs. Curr Chall Thorac Surg 2021;3:6.