Repeat venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in an infant presenting with complex airway foreign body: a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• Repeat extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) can be used to support lung recovery after complex airway foreign body removal in an infant.

What is known and what is new?

• The use of ECMO to manage airway foreign body aspiration in children has been previously reported in the literature.

• This case describes the use of VV-ECMO for a second time in the same patient in order to protect the lungs from positive-pressure ventilation in the setting of an air leak.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Risks and benefits must be considered when deciding optimal timing of decannulation in an infant requiring ECMO for complex airway foreign body removal.

• Repeat ECMO may be considered to support lung recovery in children who have been decannulated after requiring ECMO for complex airway foreign body removal.

Introduction

Background

Foreign body aspiration can cause significant morbidity and mortality in young children, and is one of the most common causes of accidental death in children under age two (1,2). In many cases, rigid bronchoscopy is required for removal of the foreign body (3). In some scenarios, spontaneous ventilation can be maintained, while in others, positive pressure ventilation is required. In either case, retrieval of the foreign body from the airway can render the airway transiently narrowed or in some cases fully obstructed. In situations which threaten total airway obstruction, venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) can provide a means of ensuring gas exchange (1).

Rationale and knowledge gap

The use of ECMO to manage airway foreign body aspiration in children has been previously reported in the literature (1). The use of repeat ECMO has also been reported in the literature, such as in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia or cardiac pathology (4,5). However, to our knowledge, this is the first case report of repeat ECMO in a child with airway foreign body aspiration.

Objective

The objectives of this case report are to describe the use of VV-ECMO to facilitate gas exchange during removal of an airway foreign body from a pediatric patient and to additionally highlight the utility of VV-ECMO to support lung recovery in the same patient later in his clinical course. Written Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization and informed consent for publication have been obtained from the patient’s parents. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts-24-1/rc).

Case presentation

A previously healthy, 10 kg, 9-month-old male presented to our pediatric operating room with acute hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to aspiration of a thumbtack. The infant presented initially to the emergency department at an outside facility and was found to be in severe respiratory distress. He was taken emergently to their operating room where, after inability to visualize a foreign object in the supraglottic region, several attempts at intubation were made. During the first attempt, which utilized video laryngoscopy, the endotracheal tube was unable to pass through the glottis secondary to distal obstruction. Immediately following the second attempt, which utilized direct laryngoscopy, the patient experienced significant desaturation and subsequent cardiopulmonary arrest. Return of spontaneous circulation was achieved after approximately nine minutes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, during which time adequate oxygenation was maintained with bag-mask ventilation. During the resuscitation, the foreign body became dislodged from the trachea into the left mainstem bronchus, permitting intubation of the trachea with a 4.0 cuffed endotracheal tube with the assistance of a rigid ventilating bronchoscope. He was then transferred to our facility by helicopter for further care, during which time our facility called for the multi-disciplinary ECMO team to prepare for ECMO cannulation in the pediatric operating room (Figure 1).

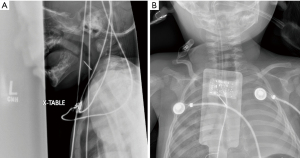

Upon arrival to our facility, the child was placed onto VV-ECMO by the pediatric surgery team to facilitate safe removal of the airway foreign body. Of note, ECMO cannulation occurred approximately 45 minutes from patient arrival to the operating room at our facility. Intra-operative radiography during ECMO cannulation demonstrated a right mainstem bronchial intubation with a foreign body in the left mainstem bronchus (Figure 2). After successful cannulation onto VV-ECMO, ventilation was weaned and the endotracheal tube was removed. A rigid bronchoscope was then inserted by the pediatric otolaryngology team to visualize the lower airway with video assistance. A red, plastic thumbtack was found to be wedged into the left mainstem bronchus, with its tip pointed up into the distal trachea (Figure 3). The head of the thumbtack was grasped with optical forceps and the thumbtack, in its entirety, was successfully removed after several attempts. During removal, the size of the thumbtack was noted to be almost equal to the diameter of the trachea at the level of the cricoid cartilage, rendering the airway functionally obstructed. The patient notably had vital signs within normal limits during removal of the airway foreign body, including oxygenation. After the thumbtack had been removed, the airway was carefully inspected for signs of injury. The mucosa appeared without evidence of bleeding or tissue damage. A new 3.5 cuffed endotracheal tube was placed, the VV-ECMO support was discontinued in the operating room, and mechanical ventilation was resumed. The infant was then transported to the pediatric intensive care unit in stable condition. The cannulas were left in place as a precautionary measure.

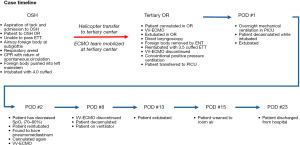

The infant was decannulated the following morning and initially tolerated mechanical ventilation with pressure support 8–10 cmH2O, positive end-expiratory pressure 8 cmH2O, and fraction of inspired oxygen of 30%. His ventilator settings were weaned throughout the course of that day, and he was then extubated to 3 liters nasal cannula with no immediate complications. His chest X-ray prior to extubation showed clear lungs, endotracheal tube tip appropriately positioned and gastric tube tip within the stomach. Approximately 12 hours later, however, he developed respiratory distress and persistent desaturation, requiring re-intubation. His saturations remained low, with oxygen saturation (SpO2) in the 70% to 80% range, and his post-intubation film was notable for a significant amount of pneumomediastinum, concerning for air leak (Figure 4). This prompted concern that positive-pressure ventilation was not an appropriate form of respiratory support, and the decision was made to bring the patient back to the operating room emergently for re-institution of VV-ECMO. After reinstitution of ECMO, bronchoscopy revealed a small, healing mucosal flap on the right glottic surface of the posterior arytenoid, but notably no visible area of mucosal disruption within the trachea or proximal mainstem bronchi. The left mainstem bronchus was noted to be filled with blood, though upon suctioning no source of active bleeding was visible. The patient was transported back to the pediatric intensive care unit. Daily chest X-rays were obtained and showed continual improvement of pneumomediastinum. He remained stable on VV-ECMO for 6 days, with improvement in blood gas measurement and minimal ECMO requirements on day 6, and therefore was weaned from support and decannulated. Mechanical ventilatory support was then slowly weaned over the course of the next 5 days and the infant was then extubated. He was weaned to room two days following extubation and did well with no sequelae from this episode of ECMO. He was discharged home on hospital day 23 in good health, with no neurologic, cardiovascular, or respiratory sequelae (Figure 5).

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Key findings

There was high clinical suspicion that removal of the foreign body posed the threat of complete airway obstruction, given the patient’s prior desaturation and subsequent cardiopulmonary arrest during the initial attempt at foreign body removal at the outside facility. Therefore, our multidisciplinary team, which included pediatric otolaryngologists, pediatric anesthesiologists, and pediatric general surgeons, decided to institute VV-ECMO prior to any interventional attempts at foreign body removal. This suspicion was confirmed on thumbtack removal as its size was noted to be almost equal to the diameter of the proximal trachea. It took several attempts to carefully maneuver the object out of the airway, along with some force to successfully pull the object through the cricoid ring. This slow and controlled extraction would not have been possible through the lumen of an endotracheal tube. Extubation and rigid bronchoscopy for removal was also unlikely to be feasible, given the inability of the child to breathe spontaneously around the occluding object. As they presented with poor saturations despite intubation and 100% fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), they also would not have tolerated the apneic periods for intermittent ventilation. Additionally, patient had already underwent cardiopulmonary resuscitation prior to arrival to our facility, and therefore was at increased risk of ongoing episodes of desaturation and hypoxia. The use of VV-ECMO to provide temporary gas exchange and permit safe removal of an airway foreign body has been previously described, though reports are limited (1,6). Our case supports the use of VV-ECMO in this clinical scenario.

We additionally describe the use of VV-ECMO for a second time in the same patient in order to protect the lungs from positive-pressure ventilation in the setting of an air leak. The mechanism for developing a significant pneumomediastinum early in the infant’s clinical course after decannulation and extubation is unclear. There were no overt signs of airway injury visualized on initial bronchoscopy after foreign body removal, or on subsequent bronchoscopy after his second ECMO cannulation. It is possible that the object itself, given its sharp point and movement through the airway, caused damage to the distal trachea or proximal left main bronchus that was unable to be visualized with direct inspection, but then became evident after the application of positive pressure ventilation and the use of relatively high inspiratory pressures in the setting of acute respiratory decompensation. The use of VV-ECMO for a second time in this patient allowed for maintenance of gas exchange with protection of the airway from volutrauma and barotrauma caused by mechanical ventilation. Upon decannulation and re-institution of positive pressure ventilation, there was no re-accumulation of pneumomediastinum, and the patient tolerated continued positive pressure ventilation for several days as ventilator settings were weaned toward extubation. This case also highlights the potential for airway injury that is not immediately evident, and the importance of close surveillance after institution of positive pressure ventilation, particularly in the setting of traumatic foreign body aspiration.

Strengths and limitations

The use of ECMO is not without its drawbacks and limitations, especially in the infant population with relatively smaller vasculature, though assistance with fluoroscopy (as used in our case) and ultrasound have been described (7). The use of ECMO has historically required systemic anticoagulation, which may not be suitable in certain clinical scenarios. However, emerging data suggests that ECMO can be used without systemic anticoagulation in some patient populations, thus expanding candidacy to additional patients, particularly those in the perioperative and trauma settings (8).

Length of ECMO runs vary from a few hours to multiple days. Reports of cases that included ECMO runs over multiple days describe that as respiratory status improved patients were weaned off ECMO (6). There is no further information provided regarding the rationale behind the duration of time on ECMO and the criteria used to determine when to wean the patient off ECMO in those cases. While a longer ECMO run could have been considered during the initial ECMO run in our patient, the patient had improved respiratory status and no indication that there was an injury to the airway. Potential complications of ECMO include gastrointestinal hemorrhage, cannulation site bleeding, arrhythmias, cardiac tamponade, central nervous system hemorrhage, and death (1). Therefore, benefits of ECMO support must be weighed against these serious risks.

Comparison with similar research

ECMO for airway foreign body removal in young children has been previously described in the literature (1,6,7). Institution of ECMO is often considered for correction of hypoxic respiratory failure separate from interventional endeavors, but also, similar to our case, has been utilized prior to starting bronchoscopy to facilitate safe extraction of airway foreign bodies. We did not find any publications referring to re-institution of ECMO after airway foreign body removal, although rationale for longer ECMO runs may include avoiding positive pressure ventilation in the setting of potential airway mucosal disruption.

Explanations of findings

This case highlights the utility of ECMO for removal of an airway foreign body in an infant, as well as the potential for late presentation of airway injury requiring repeat ECMO support.

Implications and actions needed

It is important to consider ECMO as a treatment modality, both for hypoxic respiratory failure that can been seen in pediatric foreign body aspirations, as well as to facilitate removal of these foreign bodies. When ECMO is discontinued, especially in the setting of transitioning to higher levels of positive pressure ventilation, vigilance is warranted as additional injuries may become apparent.

Conclusions

VV-ECMO cannulation prior to attempts at airway foreign body removal was determined by the multidisciplinary team to be the safest plan for management of this infant as it provided assurance of gas exchange in a situation involving the potential for total airway obstruction. Early pursuit of ECMO support should be considered in cases of foreign body aspiration in infants with respiratory instability at facilities that have ECMO capability. ECMO support can additionally be considered in situations of known or suspected airway disruption in order to avoid positive pressure ventilation and support lung recovery. Furthermore, repeat ECMO may be considered to support lung recovery in children who have been decannulated after requiring ECMO for complex airway foreign body removal.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts-24-1/prf

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts-24-1/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts-24-1/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Park AH, Tunkel DE, Park E, et al. Management of complicated airway foreign body aspiration using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78:2319-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zur KB, Litman RS. Pediatric airway foreign body retrieval: surgical and anesthetic perspectives. Paediatr Anaesth 2009;19:109-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gang W, Zhengxia P, Hongbo L, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of tracheobronchial foreign bodies in 1024 children. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:2004-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herco M, Sloan P, Vogel A, et al. Survival and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Patients with Single versus Repeat Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Runs. Am J Perinatol 2024;41:e305-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alsoufi B, Trivedi J, Rycus P, et al. Repeat Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support Is Appropriate in Selected Children With Cardiac Disease: An Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Study. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2021;12:597-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anton-Martin P, Bhattarai P, Rycus P, et al. The Use of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Life-Threatening Foreign Body Aspiration: Case Series, Review of Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry Data, and Systematic Literature Review. J Emerg Med 2019;56:523-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AlKhalifah AS, AlJassim NA. Venovenous extra corporeal life support in an infant with foreign body aspiration: A case report. Respir Med Case Rep 2022;37:101636. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Louro J, Weir JJ, Brozzi NA, et al. Treatment of Refractory Intraoperative Hypoxemia After Trauma With Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Case Report. A A Pract 2018;11:41-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Smith LD, Pecorella SH, Templeton TW, Vishneski SR. Repeat venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in an infant presenting with complex airway foreign body: a case report. Curr Chall Thorac Surg 2024;6:14.