Implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery program for lung resection

Introduction

Background

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), an evidence-based multimodal protocol of perioperative care, was firstly introduced in the late 1990s, and has been increasingly implemented in most surgical specialties. Over the years, ERAS pathways were seen to be effective in reducing hospital length of stay (LOS) and postoperative complication rates (1).

Comprehensive ERAS pathways encompass all phases of perioperative care, from initial consultation with a surgical team to post-operative recovery. Multiple improvements and efficiencies at every step in the peri-operative treatment trajectory are adopted in an evidence-based manner by a multidisciplinary team. These care elements are believed to have synergistic effects on the attenuation of operative stress responses and the protection of baseline function status, leading to an accelerated recovery (2,3). Individual care elements may not necessarily have significant benefits when studied in isolation, but their combination with other elements of the pathway is thought to have a synergistic effect (3).

Rationale and knowledge gap

In recent years, specific ERAS pathways for thoracic surgery have been published, with most reporting benefits such as shorter LOS, lower hospital costs, and fewer pulmonary and cardiac complications (4-8). In 2019, the European Society of Thoracic Surgery (ESTS) published the Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery (9). These comprehensive guidelines introduced 45 evidence-based recommendations for the ERAS protocol covering 21 areas of peri-operative care. These recommendations have formed the foundation for many ERAS protocols developed in recent years. Several systematic reviews have suggested various degrees of favorable outcomes regarding LOS, hospitalization costs, and reduced complications with ERAS protocols in lung surgery (10-12). However, these reviews also highlighted significant heterogeneity, which weakens the overall findings. This variability presents challenges in implementing, evaluating, and comparing ERAS protocols. The process of implementing a protocol is complex (4,13). Across countries, healthcare systems, and institutions, the emphasis on specific ERAS elements may differ. Variations exist in how protocol compliance is measured, which outcomes are evaluated, and how those outcomes are assessed. Indeed, the literature reports considerable variability in the extent to which ERAS guidelines are applied in clinical practice (5-8,14).

Objective

In this clinical practice review, we have selected seven perioperative elements from the ESTS guidelines that in our view are specific or essential to lung surgery. Based on a PubMed search for recent publications (from the past five years) on each topic, as well as the ESTS guidelines, we provide a brief discussion and expand on our clinical practice at the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC).

Key elements of ERAS in lung resection

Preoperative assessment and counselling

Preoperative counselling helps to set expectations about surgical and anaesthetic procedures and may diminish fear, fatigue and pain and enhance recovery and early discharge (15). Ideally patients should receive information in written, electronic, and oral formats. As in most surgeries, the preoperative consultation is also an opportunity to detect laboratory abnormalities and treat them if reversable, stratify the surgical risk, and address potential behavioral changes such as smoking cessation (16,17).

Pulmonary functions, preoperative exercise and prehabilitation

Forced expiratory volume at first second (FEV1) is essential parameter when evaluating patients for lung resection, and predicted postoperative FEV1 (ppoFEV1) has been shown to correlate with the risk of morbidity and mortality for lung surgery since the 1980s (18-23), although the majority of the surgeries in these studies were thoracotomies. In a 2009 retrospective observational study, FEV1 was an independent predictor of respiratory morbidity for thoracotomy patients but not for those treated with a thoracoscopic approach. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients, the measured postoperative FEV1 is higher than the evaluated ppoFEV1 (24-30), rendering it less reliable for this population. Carbon monoxide lung diffusion capacity (DLCO) has consistently been shown to play a central role in risk stratification before lung resection. Many studies have found predicted postoperative DLCO (ppoDLCO) to be a significant predictor of pulmonary complications and mortality in both patients with and without COPD (31-38). Nevertheless, low DLCO and/or FEV1 currently do not exclude a patient from lung resection surgery but are an indicator of the need for further investigation in the form of a cardiopulmonary exercise test, with low maximum rate of oxygen consumption attainable during physical exertion (VO2max) (threshold ranging from 10–15 mL/kg/min in different trials) as a predictor of postoperative complications, pulmonary complications, and morbidity (39-42). In conclusion, poorer preoperative exercise capacity, and poor pulmonary function in particular, is associated with worse long- and short-term clinical outcomes, including postoperative complications, LOS, and survival following curative lung cancer surgery (42-45).

Optimizing these physiological parameters prior to surgery make sense as an approach to improve recovery in patients undergoing lung resection. Indeed, the benefit of pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with severe COPD in the absence of planned surgery is well characterized (46). Preoperative physical conditioning, or prehabilitation, is the process of enhancing the functional and physiological capacity of an individual to enable them to withstand a stressful event and may aid in recovery after surgery. In colorectal surgery, prehabilitation has been shown to be effective in returning a patient to baseline function prior to a surgical insult (47,48). Although shown to be beneficial (49-52), study heterogeneity, the exact duration, intensity, structure, and patient selection to achieve maximum efficacy is uncertain. Studies report an improvement in peak oxygen consumption, lung function, and in functional capacity (measured with the 6-minute walk test) from baseline to post-intervention (52).

A Randomized Controlled Trial conducted at The Montreal General Hospital, demonstrated that home-based multimodal prehabilitation program 4 weeks prior to lung resection surgery was as effective in recovering functional capacity as the post-operative rehabilitation with the same multimodal intervention (53). The program consisted of moderate aerobic and resistance exercises in a home base setting, and included nutritional counseling with whey protein supplementation, and anxiety-reduction strategies. The prehabilitation program is an important tool in our arsenal when dealing with high-risk patients. Moreover, the time of treatment during neoadjuvant systemic therapy offers an ideal opportunity to improve the baseline functional status of the patient in preparation for an eventual surgery. At The Montreal General Hospital a significant portion of patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy utilized this program (54).

Pain management

Proper pain management is vital after thoracic surgery, as pain can be debilitating and lead to poor outcomes, such as respiratory complications, longer hospital stays, poor quality of life, and chronic post-thoracotomy pain syndrome. A multimodal analgesic strategy is required to keep the patient comfortable, allow early mobilization, and reduce the risk of pulmonary complications. Avoidance of opioids allow better post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) control and quick return to oral diet. Inadequate analgesia following either VATS or thoracotomy can exacerbate a compromised respiratory status. It may lead to respiratory failure secondary to splinting or pneumonia as a result of an ineffective cough and poor clearance of secretions. Pain increases immediate risks to the patient of hypoxaemia, hypercarbia, increased myocardial work, arrhythmias, and ischemia. Therefore, an enhanced recovery pathway for thoracic surgery must combine multimodal approach with systemic, regional analgesia and local anaesthetic techniques while attempting to avoid opioids and their side effects (55). Patient education is also important as well-informed patients may experience less pain (56).

Intraoperative regional analgesia

Historically, thoracic epidural analgesia was considered gold standard in thoracic surgery, as it was helpful in reducing pulmonary complications, although in itself has adverse effects such as urinary retention, hypotension, and muscular weakness (57). As surgical and anaesthetic techniques continue to develop and offer efficient and safe alternatives, the role of epidural anesthesia in thoracic surgery is quickly diminishing. A variety of novel techniques are currently routinely used and investigated worldwide, such as paravertebral analgesia, intercostal catheters and blocks, serratus anterior plane block, and erector spinae plane block. These techniques have been shown to provide an effective analgesia, reduce post-operative opioid consumption, and have low complication profile (55,58-65). These techniques can be used in conjuncture, and the method of choice based on operator preference and experience with the specific techniques.

At The Montreal General Hospital, our regional anesthesia of choice is usually an ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block, performed by the anesthetist prior to surgery, plus intercostal block performed by the surgeon during the operation.

Post-operative multimodal analgesia

Postoperatively, a multimodal analgesic regimen should be employed, aiming to minimize the use of opioids. The use of additive or synergistic effects of different types of analgesics, should ideally allow the side effects of individual drugs to be minimized while potentiating their positive effects and reducing the use of opioids.

Acetaminophen is a vital part of postoperative pain control and can be administered either intravenously or orally (66). It has been shown that adding acetaminophen after major can reduce morphine consumption by 20% but did not decrease the incidence of morphine-related adverse effects (67). Acetaminophen at clinical doses has few contraindications or side effects. It is considered safe for patients at risk of renal failure (68). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in combination with acetaminophen are more effective than either drug alone (69). NSAIDs have been used to control post-thoracotomy pain (70) and significantly improve pain control in patients receiving systemic opioids (71,72). The risk of Renal failure is a common reason for avoidance of NSAIDs patients.

Opioids, while beneficial in providing analgesia and prevent splinting, can have detrimental effects (PONV, constipation, sedation and the suppression of ventilation and coughing). Therefore, their use, including patient-controlled analgesia, should be kept to a minimum or avoided when possible.

Surgical technique

Although minimally invasive techniques like VATS and robotic surgery are becoming increasingly popular, a significant number of pulmonary resections worldwide are still performed using thoracotomy. Adoption of the technique was slow, with debates over the lack of evidence regarding the safety and oncologic outcomes (mainly, accuracy and extension of lymph node dissection). Although over the years, studies showed that minimally invasive techniques are associated with favorable outcomes, such as less pain, better shoulder function, earlier mobilization, shorter LOS, better preservation of pulmonary function and better quality of life (73-75), until recently the scarcity of randomised control trials has hindered the adoption of the techniques. Recently, a large UK multicenter randomized controlled trial, the VIOLET trial, was published. In this study, participants were blinded to the surgical approach (VATS versus thoracotomy) until hospital discharge. The trial demonstrated that VATS lobectomy was associated with less pain, fewer complications, and improved quality of life, without compromising oncologic outcomes (74). The clinical benefits of a minimally invasive approach are particularly evident in high-risk patients with poor predicted postoperative lung function (76). At The Montreal General Hospital, we use VATS for most of our patients, including post neoadjuvant and complex resections (77) as well as for locally advanced disease.

Minimal invasive thoracic surgery is a constantly evolving field, with a variety of techniques. The biportal and single portal approaches are increasingly replacing the traditional triportal VATS, maintaining that by decreasing the number of accesses and consequently reducing the number of damaged intercostal nerves, an additional advantage would be obtained in term of postoperative pain. The subxiphoid and subcostal approaches avoid the intercostal nerves, decreasing post-operative pain. On the other hand, an increased risk of bleeding has been reported in subxiphoid VATS lobectomy, and it requires highly experienced thoracoscopic surgeons and adequate instrumentation (78).

Robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) is the other main approach in thoracic minimal invasive surgery, and it is increasingly used worldwide. The robotic advantages compared to VATS are binocular visualization allowing an excellent high-definition three-dimensional view of the operating field, and the degrees of freedom of robotics instruments compared to the straight rigid ones used by VATS. The main limits are high costs, the availability in peripherical structures and longer learning curve in surgeons without solid mini-invasive background (79).

Studies comparing the different methods have not consistently shown significant advantage of one over the other (80-82). The debate over these methods will probably continue to exist over the next years, with surgeons using the approaches in which they feel comfortable and safe while operating.

Chest drain management

Post-operative chest tubes are an important element of recovery after lung resection surgery, as they can cause pain, reduced pulmonary function and immobility, irrespective of the surgical approach (83). Minimising chest tube number and duration is an important part of an ERAS program.

Surgical technique

Prevention is the first step in order to minimize post-operative chest tube duration and avoid prolonged air leak. A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that fissureless technique in pulmonary lobectomy could significantly reduce the incidence of prolonged air leak and the duration of chest tube (84,85). Fibrin glue, absorbable meshes, and various surgical sealants have been reported and commercially advocated as preventive measures for air leaks. However, they have yet to be routinely adopted, possibly due to concerns about cost or effectiveness. In The Montreal General Hospital, whenever possible, the lobectomies are performed in fissureless technique. We do not routinely use any sealers.

Suction versus water seal

The evidence regarding the use of external suction is conflicting (86-88). While no suction has been shown to be effective in some circumstances at reducing the duration of air leak, presumably by decreasing the airflow (89,90), the absence of suction may be ineffective in draining large air leaks and has been associated with increased risk of other complications (particularly pneumonia and arrhythmia) (91). At The Montreal General Hospital, we employ suction judiciously, with the default choice of water seal.

Digital drainage systems

Digital drainage systems, while expensive, have several advantages over a traditional water seal. They are light, compact, able to objectively quantify the volume of air leak and have a built-in suction pump, so do not need to be attached to wall suction, should suction be required, favouring early patient mobilization (92). Digital air leak tracking and its accuracy can allow chest drain removal criteria using shorter intervals (93). In The Montreal General Hospital we use traditional water seal device.

Pleural fluid drainage

Historically, the threshold for removal of chest tube post-operatively was absence of air leak and less than approximately 200 mL/day, but studies on more aggressive chest drain removal strategies have been shown to be safe. A non-chylous fluid threshold of 450 mL/day after thoracotomy was associated with only a 0.55% readmission rate for recurrent symptomatic pleural effusion (94). A higher threshold of 500 mL/day following VATS lobectomy resulted in an incidence of clinically relevant recurrent effusions (needing drainage or aspiration) in only 2.8% of patients (95). In the last several years we have used in The Montreal General Hospital the threshold of less than 800 mL of non-bloody, non-chylous fluid with low readmissions and complication rate (96).

Number of chest tubes

In recent years there is less use of the traditional 2 chest tubes after lung resection. Several randomized trials have demonstrated that the use of a single chest tube after lobectomy is safe and effective with no differences in residual pleural effusion or the need to reinsert a chest tube but is significantly less painful than 2 drains (97-99). Some surgeons have even reported safely omitting the chest drain or removing it in the operating room in anatomical lung resections (100). However, while this approach is becoming more common in minor thoracic surgeries and wedge resections (96,97), it has yet to demonstrate its safety and gain widespread acceptance in major lung resections. Our standard lobectomy patient will have one chest tube.

Early mobilization

Early mobilization is an important part of ERAS and is encouraged even though it is difficult to prove its benefit as standalone contributor in the post-lung resection recovery (51,101,102). Bed rest is associated with increased pulmonary complications (atelectasis and pneumonia) and increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) (103,104). Our patients are encouraged to walk as soon as possible with our physical therapists, many of them at the day of the surgery.

Incentive spirometry

Post-operative incentive spirometry it is used in many ERAS programs, including ours. Although it has not been shown to reduce post-operative pulmonary complications or LOS when compared to other chest rehabilitation strategies (105), it is a relatively inexpensive intervention that motivates many patients to perform regular breathing exercises without our team help. Incentive spirometry may have a benefit in higher-risk patient populations such as those with COPD, but further studies are required.

Discussion and McGill Enhanced Recovery Program for Lung Surgery

ERAS pathways aim to encompass multiple aspects of the patient trajectory, including the preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative management. The multitude of these steps and variability among centers and surgeons make it challenging to assess the impact of individual interventions or the pathway as a whole. Additionally, some interventions included in lung surgery ERAS protocols are becoming outdated as advancements and new techniques emerge each year (106). For instance, practices regarding the number of chest drains and removal criteria have evolved over time. Similarly, thoracic epidural analgesia, once commonly used in ERAS protocols, is now rarely employed due to the adoption of newer regional block techniques. Even with those limitations, it is clear that ERAS pathways have many advantages without compromising patient care, as elaborated above. Also, it reduces health-care system costs, and the cost burden on the patient and caregiver after discharge (107). ERAS implementation process can be assisted and evaluated by a value-based health care approach as a more comprehensive method of assessing costs and outcome of lung surgery. This approach combines well-defined key-performance indicators of patient outcome and measures them, while taking the costs of care into consideration (108-110).

The MUHC had adopted ERAS pathway for lung surgery in 2012. Funding was provided by the Department of Surgery, providing a full time ERAS nurse. We have shown, for lung as well as other procedures (e.g., esophagectomy, colectomy), the significant economic savings to both the hospital system as well as to the society as a whole by having patients enrolled in ERAS pathways that far outweigh the costs of the enhanced recovery program (107,111,112). Our early results showed reduction in LOS and complications with no difference in readmissions (113). When we looked retrospectively at our VATS lobectomy patients over the years, more of them were discharged home during the first 23 hours after the implementation of ERAS protocols (96). Our ERAS pathways continue to constantly evolve. As an example, our cut-off for removing chest tube has changed from 300 mL/day of non-bloody non-chyle drainage to a more lenient 800 mL/day. VATS surgery is performed where possible, also for many patients with locally advanced disease (stage II/III), and patients after neoadjuvant treatment (114).

Our team is constantly searching for ways to lower complications and LOS, while improving the patient experience. In a trial conducted in The Montreal General Hospital (115), patients were connected to portable drainage devices after anatomical lung resection surgery and underwent clamp test on post-operative day 1 (POD1). Patients who failed the clamp test were discharged home with the portable device and were followed electively at The Montreal General Hospital Thoracic Surgical Clinic. POD1 discharge rate was 72% in Portable drainage group vs. 15% the standard care group. There were no significant differences in length of indwelling chest-tube, rate of discharge with chest-tube, post-operative complications, or readmissions.

In 2023, we conducted a Phase I Safety and Feasibility Pilot Study of Same-Day Discharge after VATS Anatomical Lung or Wedge Resection (VALUE) trial, yet to be published. After consent and education, we aimed for the patients to be discharged home on the day of the surgery with a portable drainage device, and to come back to The Montreal General Hospital Thoracic Surgical Clinic 2 days after discharge for clamp test and chest tube removal when possible. Same day discharge was achieved in 18 (95%) out of 19 patients, with no grade 3–4 complications or readmissions. Thirteen (68%) patients underwent anatomical lung resections (lobectomy or segmentectomy). We plan to assess the 23 hours discharge pathway and same day discharge pathway on a larger scale, aiming to implement them for more of our patients.

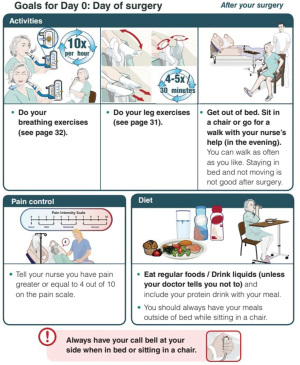

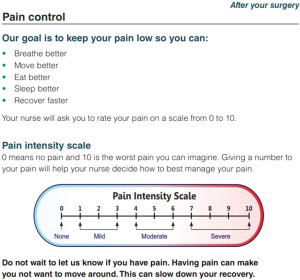

Our current pathway principles, as shown in Table 1, illustrate the pre-operative patient education. Patients receive a booklet outlining their expected journey before, during and after their surgery. Figures 1,2 are examples taken from the patient education website (https://www.muhcpatienteducation.ca/DATA/GUIDE/163_en~v~lung-surgery-montreal-general-hospital.pdf).

Table 1

| Preoperative |

| Education (including appointments with the surgeon, nurse, and anesthetist) |

| Prehabilitation when needed and for neoadjuvant patients |

| Admission on the day of surgery |

| Perioperative |

| Prophylactic antibiotics |

| No urinary catheter |

| No epidural (even for thoracotomy) |

| Regional anesthesia (ESP block and intercostal block) |

| MIS when possible (VATS, RATS) |

| Single small caliber drain |

| Postoperative |

| Early mobilization |

| Incentive spirometry |

| Opioid sparing multimodal analgesia |

| Chest drain: water seal, early removal |

ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; ESP, erector spinae plane; MIS, minimal invasive surgery; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery; RATS, robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Pain management and early mobilization are crucial components in thoracic surgery enhanced recovery, and many aspects of our protocol aim for these goals. A standard lobectomy patient at The Montreal General Hospital will undergo VATS surgery, with regional anesthesia (erector spinae plane block preoperatively by the anaesthesia team plus intraoperative intercostal block by the surgeon). No urinary catheter is inserted, and patient will have one chest tube which we aim to remove as soon as possible (no air leak and less than 800 mL/day of non-bloody non-chyle fluid). We try to avoid opiates, using them only when needed. Patient education and managing their expectations is also important in advancing them to early mobilization. Complications are documented prospectively and graded using the Ottawa Thoracic Morbidity and Mortality classification system (116).

Conclusions

In recent years, ERAS protocols for lung surgery have been established and studied. However, the wide range of possible interventions and the variability among centers and surgeons make it challenging to evaluate the impact of individual interventions or entire pathways. Despite these limitations, it is evident that ERAS pathways offer significant advantages without compromising patient care. The implementation of ERAS protocols in lung surgery is a multidisciplinary process that is both feasible and safe.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Donna E. Maziak and Patrick J. Villeneuve) for the series “Comprehensive Lung Cancer Care: A Continuum” published in Current Challenges in Thoracic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts-24-9/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts-24-9/coif). The series “Comprehensive Lung Cancer Care: A Continuum” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Nicholson A, Lowe MC, Parker J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery programmes in surgical patients. Br J Surg 2014;101:172-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth 1997;78:606-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg 2008;248:189-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dyas AR, Stuart CM, Bronsert MR, et al. Anatomic Lung Resection Outcomes After Implementation of a Universal Thoracic ERAS Protocol Across a Diverse Health Care System. Ann Surg 2024;279:1062-9. [PubMed]

- The Impact of Enhanced Recovery Protocol Compliance on Elective Colorectal Cancer Resection: Results From an International Registry. Ann Surg 2015;261:1153-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez M, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Perentes JY, et al. An enhanced recovery after surgery program for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery anatomical lung resections is cost-effective. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:5879-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forster C, Doucet V, Perentes JY, et al. Impact of an enhanced recovery after surgery pathway on thoracoscopic lobectomy outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer patients: a propensity score-matched study. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2021;10:93-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forster C, Doucet V, Perentes JY, et al. Impact of Compliance With Components of an ERAS Pathway on the Outcomes of Anatomic VATS Pulmonary Resections. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2020;34:1858-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Batchelor TJP, Rasburn NJ, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, et al. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2019;55:91-115. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldblatt JG, Bibo L, Crawford L. Does Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocols Reduce Complications and Length of Stay After Thoracic Surgery: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cureus 2024;16:e59918. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fiore JF Jr, Bejjani J, Conrad K, et al. Systematic review of the influence of enhanced recovery pathways in elective lung resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:708-715.e6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li S, Zhou K, Che G, et al. Enhanced recovery programs in lung cancer surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Manag Res 2017;9:657-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Meyenfeldt EM, van Nassau F. Implementing an enhanced recovery after thoracic surgery programme: just having a protocol is not enough. J Thorac Dis 2023;15:1-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Meyenfeldt EM, de Betue CTI, van den Berg R, et al. Wide Variation in Perioperative Care in Anatomical Lung Resections in the Netherlands: A National Survey. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;32:1101-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Darville-Beneby R, Lomanowska AM, Yu HC, et al. The Impact of Preoperative Patient Education on Postoperative Pain, Opioid Use, and Psychological Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Can J Pain 2023;7:2266751. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barrera R, Shi W, Amar D, et al. Smoking and timing of cessation: impact on pulmonary complications after thoracotomy. Chest 2005;127:1977-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mason DP, Subramanian S, Nowicki ER, et al. Impact of smoking cessation before resection of lung cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database study. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:362-70; discussion 370-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakahara K, Ohno K, Hashimoto J, et al. Prediction of postoperative respiratory failure in patients undergoing lung resection for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1988;46:549-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Markos J, Mullan BP, Hillman DR, et al. Preoperative assessment as a predictor of mortality and morbidity after lung resection. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;139:902-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Magdeleinat P, Seguin A, Alifano M, et al. Early and long-term results of lung resection for non-small-cell lung cancer in patients with severe ventilatory impairment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;27:1099-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Licker MJ, Widikker I, Robert J, et al. Operative mortality and respiratory complications after lung resection for cancer: impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and time trends. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:1830-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson MK, Siddique J, Karrison T. Modeling major lung resection outcomes using classification trees and multiple imputation techniques. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:1085-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry MF, Hanna J, Tong BC, et al. Risk factors for morbidity after lobectomy for lung cancer in elderly patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1093-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carretta A, Zannini P, Puglisi A, et al. Improvement of pulmonary function after lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer in emphysematous patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;15:602-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santambrogio L, Nosotti M, Baisi A, et al. Pulmonary lobectomy for lung cancer: a prospective study to compare patients with forced expiratory volume in 1 s more or less than 80% of predicted. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:684-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Al Refai M, Monteverde M, et al. Predictors of early morbidity after major lung resection in patients with and without airflow limitation. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:999-1003. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sekine Y, Iwata T, Chiyo M, et al. Minimal alteration of pulmonary function after lobectomy in lung cancer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76:356-61; discussion 362. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Refai M, Salati M, et al. Predicted versus observed FEV1 and DLCO after major lung resection: a prospective evaluation at different postoperative periods. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1134-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Sabbatini A, Xiume' F, et al. A model to predict the decline of the forced expiratory volume in one second and the carbon monoxide lung diffusion capacity early after major lung resection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2005;4:61-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Korst RJ, Ginsberg RJ, Ailawadi M, et al. Lobectomy improves ventilatory function in selected patients with severe COPD. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:898-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson MK, Little L, Rizzo L, et al. Diffusing capacity predicts morbidity and mortality after pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1988;96:894-900. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry MF, Villamizar-Ortiz NR, Tong BC, et al. Pulmonary function tests do not predict pulmonary complications after thoracoscopic lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:1044-51; discussion 1051-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson MK, Reeder LB, Mick R. Optimizing selection of patients for major lung resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;109:275-81; discussion 281-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santini M, Fiorello A, Vicidomini G, et al. Role of diffusing capacity in predicting complications after lung resection for cancer. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;55:391-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson MK, Gaissert HA, Grab JD, et al. Pulmonary complications after lung resection in the absence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the predictive role of diffusing capacity. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;138:1297-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Refai MA, Salati M, et al. Carbon monoxide lung diffusion capacity improves risk stratification in patients without airflow limitation: evidence for systematic measurement before lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29:567-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bolliger CT, Jordan P, Solèr M, et al. Exercise capacity as a predictor of postoperative complications in lung resection candidates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:1472-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson MK, Vigneswaran WT. Diffusing capacity predicts morbidity after lung resection in patients without obstructive lung disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1158-64; discussion 1164-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loewen GM, Watson D, Kohman L, et al. Preoperative exercise Vo2 measurement for lung resection candidates: results of Cancer and Leukemia Group B Protocol 9238. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:619-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bayram AS, Candan T, Gebitekin C. Preoperative maximal exercise oxygen consumption test predicts postoperative pulmonary morbidity following major lung resection. Respirology 2007;12:505-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Belardinelli R, Refai M, et al. Peak oxygen consumption during cardiopulmonary exercise test improves risk stratification in candidates to major lung resection. Chest 2009;135:1260-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Licker M, Schnyder JM, Frey JG, et al. Impact of aerobic exercise capacity and procedure-related factors in lung cancer surgery. Eur Respir J 2011;37:1189-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Friedel G, Fritz P, Goletz S, et al. Postoperative survival of lung cancer patients: are there predictors beyond TNM? Anticancer Res 2013;33:1609-19. [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Pompili C, Salati M, et al. Preoperative maximum oxygen consumption is associated with prognosis after pulmonary resection in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:238-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones LW, Watson D, Herndon JE 2nd, et al. Peak oxygen consumption and long-term all-cause mortality in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 2010;116:4825-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD003793. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillis C, Li C, Lee L, et al. Prehabilitation versus rehabilitation: a randomized control trial in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Anesthesiology 2014;121:937-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayo NE, Feldman L, Scott S, et al. Impact of preoperative change in physical function on postoperative recovery: argument supporting prehabilitation for colorectal surgery. Surgery 2011;150:505-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cavalheri V, Granger C. Preoperative exercise training for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD012020. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crandall K, Maguire R, Campbell A, et al. Exercise intervention for patients surgically treated for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): a systematic review. Surg Oncol 2014;23:17-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mainini C, Rebelo PF, Bardelli R, et al. Perioperative physical exercise interventions for patients undergoing lung cancer surgery: What is the evidence? SAGE Open Med 2016;4:2050312116673855. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sebio Garcia R, Yáñez Brage MI, Giménez Moolhuyzen E, et al. Functional and postoperative outcomes after preoperative exercise training in patients with lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2016;23:486-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferreira V, Minnella EM, Awasthi R, et al. Multimodal Prehabilitation for Lung Cancer Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2021;112:1600-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmid S, Minnella EM, Pilon Y, et al. Neoadjuvant Prehabilitation Therapy for Locally Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Optimizing Outcomes Throughout the Trajectory of Care. Clin Lung Cancer 2022;23:593-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marshall K, McLaughlin K. Pain Management in Thoracic Surgery. Thorac Surg Clin 2020;30:339-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Egbert LD, Battit GE, Welch CE, et al. Reduction of postoperative pain by encouragement and instruction of patients. a study of doctor-patient rapport. N Engl J Med 1964;270:825-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cook TM, Counsell D, Wildsmith JA, et al. Major complications of central neuraxial block: report on the Third National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Br J Anaesth 2009;102:179-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Andrilli A, Ibrahim M, Ciccone AM, et al. Intrapleural intercostal nerve block associated with mini-thoracotomy improves pain control after major lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29:790-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies RG, Myles PS, Graham JM. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy and side-effects of paravertebral vs epidural blockade for thoracotomy--a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth 2006;96:418-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joshi GP, Bonnet F, Shah R, et al. A systematic review of randomized trials evaluating regional techniques for postthoracotomy analgesia. Anesth Analg 2008;107:1026-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeung JH, Gates S, Naidu BV, et al. Paravertebral block versus thoracic epidural for patients undergoing thoracotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2:CD009121. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scarfe AJ, Schuhmann-Hingel S, Duncan JK, et al. Continuous paravertebral block for post-cardiothoracic surgery analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:1010-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luketich JD, Land SR, Sullivan EA, et al. Thoracic epidural versus intercostal nerve catheter plus patient-controlled analgesia: a randomized study. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:1845-9; discussion 1849-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finnerty DT, McMahon A, McNamara JR, et al. Comparing erector spinae plane block with serratus anterior plane block for minimally invasive thoracic surgery: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Anaesth 2020;125:802-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koo CH, Lee HT, Na HS, et al. Efficacy of Erector Spinae Plane Block for Analgesia in Thoracic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2022;36:1387-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cook TM, Riley RH. Analgesia following thoracotomy: a survey of Australian practice. Anaesth Intensive Care 1997;25:520-4. [PubMed]

- Remy C, Marret E, Bonnet F. Effects of acetaminophen on morphine side-effects and consumption after major surgery: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth 2005;94:505-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dahl V, Raeder JC. Non-opioid postoperative analgesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2000;44:1191-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ong CK, Seymour RA, Lirk P, et al. Combining paracetamol (acetaminophen) with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a qualitative systematic review of analgesic efficacy for acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 2010;110:1170-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keenan DJ, Cave K, Langdon L, et al. Comparative trial of rectal indomethacin and cryoanalgesia for control of early postthoracotomy pain. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;287:1335-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rhodes M, Conacher I, Morritt G, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for postthoracotomy pain. A prospective controlled trial after lateral thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992;103:17-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavy T, Medley C, Murphy DF. Effect of indomethacin on pain relief after thoracotomy. Br J Anaesth 1990;65:624-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials on safety and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2553-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Long H, Tan Q, Luo Q, et al. Thoracoscopic Surgery Versus Thoracotomy for Lung Cancer: Short-Term Outcomes of a Randomized Trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;105:386-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bendixen M, Jørgensen OD, Kronborg C, et al. Postoperative pain and quality of life after lobectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or anterolateral thoracotomy for early stage lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:836-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burt BM, Kosinski AS, Shrager JB, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with acceptable morbidity and mortality in patients with predicted postoperative forced expiratory volume in 1 second or diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide less than 40% of normal. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:19-28, dicussion 28-29.e1.

- Sorin M, Huynh C, Rokah M, et al. Neoadjuvant Targeted Therapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Its Impact on Surgical Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg Short Rep 2023;1:102-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, Lirio F, Sesma J, et al. Subxiphoid complex uniportal video-assisted major pulmonary resections. J Vis Surg 2017;3:93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee EC, Lazzaro RS, Glassman LR, et al. Switching from Thoracoscopic to Robotic Platform for Lobectomy: Report of Learning Curve and Outcome. Innovations (Phila) 2020;15:235-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen Y, Wang H, Feng M, et al. Single- versus multiple-port thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer: a propensity-matched study†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:i48-53. [PubMed]

- Tosi D, Nosotti M, Bonitta G, et al. Uniportal and three-portal video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy: analysis of the Italian video-assisted thoracic surgery group database. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2019;29:714-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Ameri M, Sachs E, Sartipy U, et al. Uniportal versus multiportal video-assisted thoracic surgery for lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:5152-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Refai M, Brunelli A, Salati M, et al. The impact of chest tube removal on pain and pulmonary function after pulmonary resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:820-2; discussion 823. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li SJ, Zhou K, Li YJ, et al. Efficacy of the fissureless technique on decreasing the incidence of prolonged air leak after pulmonary lobectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2017;42:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Cassivi SD, Halgren L. Risk factors for prolonged air leak after pulmonary resection. Thorac Surg Clin 2010;20:359-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deng B, Tan QY, Zhao YP, et al. Suction or non-suction to the underwater seal drains following pulmonary operation: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;38:210-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao S, Zhang Z, Aragón J, et al. The Society for Translational Medicine: clinical practice guidelines for the postoperative management of chest tube for patients undergoing lobectomy. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:3255-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coughlin SM, Emmerton-Coughlin HM, Malthaner R. Management of chest tubes after pulmonary resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Surg 2012;55:264-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cerfolio RJ, Bass C, Katholi CR. Prospective randomized trial compares suction versus water seal for air leaks. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;71:1613-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marshall MB, Deeb ME, Bleier JI, et al. Suction vs water seal after pulmonary resection: a randomized prospective study. Chest 2002;121:831-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gocyk W, Kużdżał J, Włodarczyk J, et al. Comparison of Suction Versus Nonsuction Drainage After Lung Resections: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:1119-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou L, Guo K, Shang X, et al. Advantages of applying digital chest drainage system for postoperative management of patients following pulmonary resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2023;71:1-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdul Khader A, Pons A, Palmares A, et al. Outcomes of chest drain management using only air leak (without fluid) criteria for removal after general thoracic surgery-a drainology study. J Thorac Dis 2023;15:3776-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS. Results of a prospective algorithm to remove chest tubes after pulmonary resection with high output. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;135:269-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bjerregaard LS, Jensen K, Petersen RH, et al. Early chest tube removal after video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy with serous fluid production up to 500 ml/day. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:241-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dumitra TC, Molina JC, Mouhanna J, et al. Feasibility analysis for the development of a video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) lobectomy 23-hour recovery pathway. Can J Surg 2020;63:E349-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alex J, Ansari J, Bahalkar P, et al. Comparison of the immediate postoperative outcome of using the conventional two drains versus a single drain after lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76:1046-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Caro A, Roca MJ, Torres J, et al. Successful use of a single chest drain postlobectomy instead of two classical drains: a randomized study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29:562-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okur E, Baysungur V, Tezel C, et al. Comparison of the single or double chest tube applications after pulmonary lobectomies. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;35:32-5; discussion 35-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ueda K, Hayashi M, Tanaka T, et al. Omitting chest tube drainage after thoracoscopic major lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;44:225-9; discussion 229. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castelino T, Fiore JF Jr, Niculiseanu P, et al. The effect of early mobilization protocols on postoperative outcomes following abdominal and thoracic surgery: A systematic review. Surgery 2016;159:991-1003. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Granger CL, McDonald CF, Berney S, et al. Exercise intervention to improve exercise capacity and health related quality of life for patients with Non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer 2011;72:139-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- BED REST. thrombosis, and embolism. Lancet 1958;1:465-6. [PubMed]

- Convertino VA. Cardiovascular consequences of bed rest: effect on maximal oxygen uptake. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997;29:191-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sullivan KA, Churchill IF, Hylton DA, et al. Use of Incentive Spirometry in Adults following Cardiac, Thoracic, and Upper Abdominal Surgery to Prevent Post-Operative Pulmonary Complications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Respiration 2021;100:1114-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laven IEWG, Franssen AJPM, Daemen JHT, et al. Thinking outside the "Enhanced Recovery After Surgery" box: would a more progressive, patient-tailored approach in chest tube management be next? J Thorac Dis 2023;15:1551-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paci P, Madani A, Lee L, et al. Economic Impact of an Enhanced Recovery Pathway for Lung Resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:950-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Demedts I, Himpe U, Bossuyt J, et al. Clinical implementation of value based healthcare: Impact on outcomes for lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer 2021;162:90-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horvath KA. Finding the Value in Value-Based Care. Ann Thorac Surg 2021;112:16-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Orlandi R, Scarci M, Cioffi U, et al. Multi-level analysis and evaluation of organizational improvements in thoracic surgery according to a Value-Based HealthCare approach. J Thorac Dis 2023;15:1046-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee L, Li C, Robert N, et al. Economic impact of an enhanced recovery pathway for oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 2013;100:1326-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee L, Mata J, Ghitulescu GA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Enhanced Recovery Versus Conventional Perioperative Management for Colorectal Surgery. Ann Surg 2015;262:1026-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Madani A, Fiore JF Jr, Wang Y, et al. An enhanced recovery pathway reduces duration of stay and complications after open pulmonary lobectomy. Surgery 2015;158:899-908; discussion 908-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pilon Y, Rokah M, Seitlinger J, et al. Transitioning to Neoadjuvant Therapy for Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Trends and Surgical Outcomes in a Regionalized Pulmonary Oncology Network. Clin Lung Cancer 2024;25:e133-e144.e4.

- Schmid S, Kaafarani M, Baldini G, et al. Implication of a novel postoperative recovery protocol to increase day 1 discharge rate after anatomic lung resection. J Thorac Dis 2021;13:6399-408. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seely AJ, Ivanovic J, Threader J, et al. Systematic classification of morbidity and mortality after thoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:936-42; discussion 942. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Rokah M, Ferri L. Implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery program for lung resection. Curr Chall Thorac Surg 2025;7:5.