Prognostic factors of resected lung cancer with chest wall involvement

Introduction

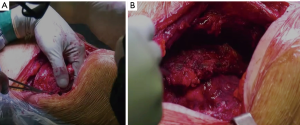

Chest wall involvement in bronchogenic carcinomas is observed by approximately 5% to 8% of resectable lung cancer (1). In these cases, patients may present a heterogeneous extent of invasion, ranging from parietal pleura infiltration to full-thickness invasion of the chest wall, with or without the involvement of neighboring anatomic structures such as intercostal space including neurovascular bundle, vertebrae, mediastinal vascular structure, as well as extra-thoracic soft tissues. As a whole, these bronchogenic carcinomas are classified as T3 or T4, depending on the involved structures (2). In such cases, extended resection is needed to maximize the chances of durable disease control (3). Demolition and reconstructive surgery stand as a mainstay in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Figure 1). Moreover, increasing the use of multimodal integrated treatment, including chemo- and radiotherapy regimen, as well as induction immunotherapy, is expected to increase the number of currently disqualified patients at presentation who can be considered eligible for curative-intent surgery after preoperative treatments.

The prognosis of patients with tumors invading the chest wall and mediastinal lymph node metastasis is poor. The five-year survival rate of T3N0 ranges from 40% to 50% in the different series, but these figures are halved in N1 patients, decreasing to one fifth in N2 patients (4,5).

Different prognostic factors have been consistently reported in the literature for those patients; incomplete resection of the tumor, presence of nodal involvement (especially in the N2 stations), depth of chest wall invasion, among others. Nevertheless, the role of other factors influencing survival is still unclear, and many questions remain partially unanswered, including the effective role of multimodality regimens or the impact of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy in completely resected chest wall invading NSCLC without nodal involvement (6-9).

A review of the literature was performed to identify prognostic factors related to long-term-survival in NSCLC, invading the chest wall.

The most essential and representative prognostic factors

N0–N1/N2

Different literature reports agree that lymph-node involvement and pathologic nodal status is the most important prognostic factors (1,5-8,10-22). Five-years survival is impacted, in the examined literature, by the presence of ipsilateral hilar (N1) or mediastinal (N2) lymph-node metastasis, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Report | Year, country/region | Report | OS (%) | N0 (%) | N+ (%) | P (univariate analysis) | Multivariate analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piehler et al. (6) | 1982, USA | Original report | 32.9 | 53.7 | 7.4 | <0.001 | – |

| McCaughan et al. (10) | 1985, USA | Original report | 40 | 56 | 21 | 0.005 | – |

| Ricci et al. (11) | 1987, Italy | Original report | 15 | 22 | N1: 12 | – | – |

| N2: 8 | |||||||

| Allen et al. (7) | 1991, USA | Original report | 26.3 | 29.1 | 11 | <0.05 | – |

| Pitz et al. (8) | 1996, Netherlands | Original report | 24 | 36 | N1: 23 | <0.05 | HR: 2.43 |

| N2: 14 | |||||||

| Downey et al. (12) | 1999, USA | Original report | 32 | 49 | N1: 27 | <0.0003 | – |

| N2: 15 | |||||||

| Chapelier et al. (13) | 2000, France | Original report | 18 | 22 | N1:9 | 0.026 | – |

| N2: 0 | |||||||

| Magdeleinat et al. (14) | 2001, France | Original report | 24 | 25 | N1: 20 | 0.05 | P=0.0006 |

| N2: 1 | |||||||

| Facciolo et al. (4) | 2001, Italy | Original report | 61.4 | 67 | 17 | 0.13 | – |

| Burkhart et al. (15) | 2002, USA | Original report | 38.7 | 44.3 | 26.3 | 0.082 | NS |

| Matsuoka et al. (16) | 2004, Japan | Original report | 34.2 | 44 | N1: 40 | 0.00019 (N0/N2) | – |

| N2: 6 | |||||||

| Doddoli et al. (17) | 2005, France | Original report | 30.7 | 40 | N1: 23 | 0.056 | NS |

| N2: 8 | |||||||

| Lin et al. (18) | 2006, Taiwan | Original report | 28.4 | 39 | 7.1 | 0.01 | – |

| Voltolini et al. (19) | 2006, Italy | Original report | 37 | 42 | 17 | 0.02 | P=0.011 |

| Lee et al. (20) | 2012, Korea | Original report | 26.3 | 37 | N1: 21 | 0.029 | P=0.0001 |

| N2: 4 | |||||||

| Deslauriers et al. (1) | 2013, Canada | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Filosso et al. (5) | 2016, Italy | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lanuti (21) | 2017, USA | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chiappetta et al. (22) | 2019, Italy | Original report | 34 | 32 | 19 | 0.5 | – |

NS, not significant.

Completeness of resection

Persistence of tumor tissue after resection and the presence of incompletely resected margins of the specimen represent another significant prognostic factor (8,14,16,19,20). The cornerstone of the surgical treatment is the complete resection (R0) without microscopic (R1) or macroscopic (R2) positive margins. R1/R2 resection is a negative impact factor on the survival of these patients, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Report | Year, country/region | Report | OS (%) | R0 (%) | R1–R2 (%) | P | Multivariate analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piehler et al. (6) | 1982, USA | Original report | 32.9 | NA | NA | – | – |

| McCaughan et al. (10) | 1985, USA | Original report | 40 | 40 | No R+ included | – | – |

| Ricci et al. (11) | 1987, Italy | Original report | 15 | NA | NA | – | – |

| Allen et al. (7) | 1991, USA | Original report | 26.3 | 33 | 15 | 0.18 | – |

| Pitz et al. (8) | 1996, Netherlands | Original report | 24 | 29 | 11 | 0.001 | NS |

| Downey et al. (12) | 1999, USA | Original report | 32 | 32 | 4 | NS | – |

| Chapelier et al. (13) | 2000, France | Original report | 18 | NA | NA | – | – |

| Magdeleinat et al. (14) | 2001, France | Original report | 24 | 24 | 13 | <0.05 | NS |

| Facciolo et al. (4) | 2001, Italy | Original report | 61.4 | 61.4 | No R+ included | – | – |

| Burkhart et al. (15) | 2002, USA | Original report | 38.7 | NA | NA | – | – |

| Matsuoka et al. (16) | 2004, Japan | Original report | 30 | 34 | 14 | 0.048 | – |

| Doddoli et al. (17) | 2005, France | Original report | 30.7 | NA | NA | – | – |

| Lin et al. (18) | 2006, Taiwan | Original report | 28.4 | NA | NA | – | – |

| Voltolini et al. (19) | 2006, Italy | Original report | 37 | 33 | 0 | 0.0001 | NS (small numbers of the case) |

| Lee et al. (20) | 2012, Korea | Original report | 26.3 | 31 | 7.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Deslauriers et al. (1) | 2013, Canada | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Filosso et al. (5) | 2016, Italy | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lanuti (21) | 2017, USA | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chiappetta et al. (22) | 2019, Italy | Original report | 34 | 45 | 30 | NS | NS |

NA, not analyzed; NR, not reported in the study; NS, not significant.

Depth of infiltration

Contiguous involvement limited to parietal pleural only, for the invasion of soft tissues with or without ribs involvement and chest wall, influences survival rate. Notably, in several studies (13,14,19) is reported that the diseases with involvement limited to parietal pleura only have a better prognosis than full-thickness involvement. Literature data are exposed in Table 3.

Table 3

| Report | Year, country/region | Report | OS (%) | Parietal pleura (%) | Full-thickness (%) |

P | Multivariate analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piehler et al. (6) | 1982, USA | Original report | 32.9 | NR | NR | NS | NS |

| McCaughan et al. (10) | 1985, USA | Original report | 40 | NR | NR | NS | – |

| Ricci et al. (11) | 1987, Italy | Original report | 15 | NA | NA | – | – |

| Allen et al. (7) | 1991, USA | Original report | 26.3 | NA | NA | – | – |

| Pitz et al. (8) | 1996, Netherlands | Original report | 24 | NA | NA | – | – |

| Downey et al. (12) | 1999, USA | Original report | 32 | 30 | 29 | NS | NS |

| Chapelier et al. (13) | 2000, France | Original report | 18 | NR | NR | 0.02 | 0.024 |

| Magdeleinat et al. (14) | 2001, France | Original report | 24 | 37 | 15 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Facciolo et al. (4) | 2001, Italy | Original report | 61.4 | 79 | 56 | NS | – |

| Burkhart et al. (15) | 2002, USA | Original report | 38.7 | 49.9 | 35 | NS | – |

| Matsuoka et al. (16) | 2004, Japan | Original report | 30 | 30 | 38 | NS | – |

| Doddoli et al. (17) | 2005, France | Original report | 30.7 | NR | NR | 0.052 | NS |

| Lin et al. (18) | 2006, Taiwan | Original report | 28.4 | 10.9 | 33.4 | NS | – |

| Voltolini et al. (19) | 2006, Italy | Original report | 37 | 43 | 8.7 | 0.003 | 0.011 |

| Lee et al. (20) | 2012, Korea | Original report | 26.3 | NR | NR | 0.148 | 0.003 |

| Deslauriers et al. (1) | 2013, Canada | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Filosso et al. (5) | 2016, Italy | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lanuti (21) | 2017, USA | Review | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chiappetta et al. (22) | 2019, Italy | Original report | 34 | 25 | 28 | 0.78 | NS |

NA, not analyzed; NR, not reported in the study; NS, not significant.

Age

Piehler et al. (6) and Magdeleinat et al. (14) agree that age >60 years represents a negative prognostic factor for NSCLC lung cancer involving the chest wall.

Number of resected ribs

Other authors found that the number of resected ribs is a prognostic factor (1,13,17,21), though it could be considered as an indirect parameter correlated to tumor size: indeed, a diameter > 5cm was associated to the extension of resection, as reported by Lee et al. (20).

The real cut-off of resected ribs is a matter of debate: according to Chapelier et al. (13) and Doddoli et al. (17), it corresponds to 2 resected ribs.

Sex

Burkhart et al. (15) reported in his study that women had better 5-year survival than men (52.9% vs. 31%, P=0.0122).

In 5–10% of the cases, bronchogenic carcinoma is accompanied by chest wall involvement. Surgical resection, whose technical feasibility was firstly described in 1947 by Coleman (23), is the critical element in the management of most patients with chest wall invading NSCLC. Regardless of pT or pN, overall 5-years survival for these patients ranges from 10% (5,11) to 61.4% (4) in the different series. Several authors tried to identify the various factors influencing survival.

The most important prognostic factor revealed in almost all analyzed works is the pathological nodal status (1,4,5-8,10-21). The presence of lymph nodal involvement strongly impacts the survival rate. In the different analyzed series, in T3 patients, N2 is a significant negative prognostic factor reducing survival (12,13) as compared to N0 (3-5). The most remarkable difference in 5-year survival between T3N0 and T3N2 (67.3% vs. 17.9%, P=0.007) is found in the report by Facciolo et al. (4). In general, the median 5-year survival rate for pT3 N0 patients is estimated at 50%; the presence of lymph nodal metastases worsens this rate up to 20–25% in N1 and below 10% in N2 patients (3,5). These results are even more surprising if we consider that the life expectancy of selected state IV patients with oligometastatic disease (brain or adrenal gland) may be superior as compared to T3N2 patients (24,25). Lymph nodal involvement is not always related to the tumor size and the depth of the chest wall (CW) invasion (3,24,25). A cytologic or histologic N2 confirmation finding (EBUS, mediastinoscopy) represents, for some authors, a strong contraindication to surgery (3). According to current clinical practice, in the presence of N2 involvement in a potentially resectable T3 lung cancer, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical re-evaluation is a valuable option (4). However, the benefit of multimodality management encompassing chemotherapy and radiotherapy in lung cancer invading the chest wall is debated. Except for superior sulcus tumors, for whom neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is a standard of care (26,27), current guidelines validate surgery as the primary treatment modality in T3–4 N0–1 NSCLC patients and limit the use of radiotherapy to the case of incomplete resection. Most interestingly, indirect evidence suggests a possible increased benefit in survival for preoperative radiotherapy in patients with T3N2 NSCLC (28). This is an important issue: since nodal staging is the primary determinant of prognosis (1,4,5-8,10-21), some authors discourage surgical resection if N2 disease is recognized (7,29), while others experience (11,12,14,30) consider that mediastinal nodal involvement should not be considered a contraindication to surgery on the basis of encouraging 15–21% survival at five years in operated patients. While a recent meta-analysis found no benefit of chemoradiation compared to induction chemotherapy in operable stage IIIA patients (31), it could be speculated that use of chemoradiation, combined with extended resection, may be of interest in the subset of patients with T3–4 N2 disease to increase the rate of complete resections.

Incompleteness of resection represents another prognostic factor (8,10,12,16,19,20). It is well known that a main goal of the surgical treatment is represented by clear surgical margins, since pathologic microscopic (R1) or macroscopic (R2) margins of the specimen represents may impair the survival of these patients. Thus, 5-year survival rates for R0 and R1/R2 resection in these patients range between 40.4–58.3% and 10.9–15.9%, respectively (8,32,33). According to Downey et al. (12), an incomplete resection, even if R1, doesn’t ensure a real curative benefit. The 3-years survival (4%) of incompletely resected patients did not significantly differ from 3-years survival of the patients undergoing no resection at all (0%). Hence, quality of the resection is capital in achieving long-term survival: Matsuoka et al. (16) stress the paramount importance of complete resection, because of a statistically significant difference in survival rate between patients receiving complete (5-years survival 34.2) or incomplete resection (14.3%).

Two other major prognostic factors are the extension of resection (number of resected ribs) (1,13,17,21) and the depth of infiltration (1,8,10,13,14,20,21). They may influence the choice of surgical technique (6-8,10-12), in particular, if tumor invasion does not extend beyond parietal pleura (14). Preoperative workup is crucial in determining the surgical technique. At present, computed tomography is frequently used to assess chest wall invasion (34); alternative imaging modalities include surgeon performed ultrasound (34) or magnetic resonance imaging (35), in particular, weighted sequences (disruption of the extrapleural fat tissue) or cine MR techniques (fixation of the tumor during respiratory motion) (35). Nevertheless, chest invasion evaluation relies mainly on intra-operative assessment of tumor adhesion to parietal pleura. Some authors conclude that patients with tumor invasion limited to parietal pleura experience improved survival—advocating for exclusive pleurectomy—if extra-pleural dissection can be obtained (10,12,20), considering the absence of significant difference in the 5-year survival between the patients with only pleural invasion, receiving extra-pleural resection and chest wall resection (20). The presence of the parietal pleura may act as a barrier to tumor infiltration; thus, the use of extra-pleural dissection can limit the extent of the resection without jeopardizing the oncological safety of the procedure (36). However, the depth of tumor infiltration and the presence of a cleavage plane with the chest wall are frequently judged on an operator-dependent basis, and intraoperative pathologic assessment is rarely contributing: hence, extra-pleural dissection might result in a potentially higher number of incomplete resections (12). Extra-pleural dissection can be safely performed in selected patients with invasion limited to parietal pleura if satisfactory dissection of pleura from the underlying osteomuscular plane can be achieved. In case of proven extension beyond parietal pleura, en bloc pulmonary and chest wall resection is required.

Finally, age >60 years (6,14) and male sex (15) have also been reported among prognostic factors; however, the confounding effect of other variables due to the small population in these studies cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

In conclusion, lung cancer invading chest wall remains a challenge for medical and surgical teams; the principal prognostic factors impacting on survival are lymph-node status, depth of disease infiltration and extension of the resection and the completeness of resection. Even if multimodality management encompassing chemotherapy and radiotherapy strategies in lung cancer invading chest wall is debated, a multidisciplinary approach, integrating surgery, neoadjuvant and adjuvant radio, and chemotherapy is the key to offer patients the best available solutions in the optimal timing.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Francesco Puma and Hon Chi Suen) for the series “Surgical Management of Chest Wall Tumors” published in Current Challenges in Thoracic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ccts.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ccts.2019.12.01/coif). The series “Surgical Management of Chest Wall Tumors” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Deslauriers J, Tronc F, Fortin D. Management of tumors involving the chest wall including pancoast tumors and tumors invading the spine. Thorac Surg Clin 2013;23:313-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. Lung. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. editors. AJCC cancer staging handbook. From the AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th edition. Chicago: Springer, 2010:299-323.

- Stoelben E, Ludwig C. Chest wall resection for lung cancer: indications and techniques. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;35:450-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Facciolo F, Cardillo G, Lopergolo M, et al. Chest wall invasion in non-small cell lung carcinoma: a rationale for en bloc resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;121:649-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filosso PL, Sandri A, Guerrera F, et al. Primary lung tumors invading the chest wall. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S855-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piehler JM, Pairolero PC, Weiland LH, et al. Bronchogenic carcinoma with chest wall invasion: factors affecting survival following en bloc resection. Ann Thorac Surg 1982;34:684-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allen MS, Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC, et al. Bronchogenic carcinoma with chest wall invasion. Ann Thorac Surg 1991;51:948-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pitz CC, Brutel de la Rivière A, Elbers HR, et al. Surgical treatment of 125 patients with non-small cell lung cancer and chest wall involvement. Thorax 1996;51:846-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Pas T, Raimondi S, Pelosi G, et al. A critical appraisal of the adjuvant chemotherapy guidelines for patients with completely resected T3N0 non-small-cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol 2010;49:480-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCaughan BC, Martini N, Bains MS, et al. Chest wall invasion in carcinoma of the lung. Therapeutic and prognostic implications. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985;89:836-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ricci C, Rendina EA, Venuta F. En bloc resection for T3 bronchogenic carcinoma with chest wall invasion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1987;1:23-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Downey RJ, Martini N, Rusch VW, et al. Extent of chest wall invasion and survival in patients with lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;68:188-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chapelier A, Fadel E, Macchiarini P, et al. Factors affecting long-term survival after en-bloc resection of lung cancer invading the chest wall. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;18:513-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Magdeleinat P, Alifano M, Benbrahem C, et al. Surgical treatment of lung cancer invading the chest wall: results and prognostic factors. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;71:1094-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burkhart HM, Allen MS, Nichols FC 3rd, et al. Results of en bloc resection for bronchogenic carcinoma with chest wall invasion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;123:670-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka H, Nishio W, Okada M, et al. Resection of chest wall invasion in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004;26:1200-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doddoli C, D'Journo B, Le Pimpec-Barthes F, et al. Lung cancer invading the chest wall: a plea for en-bloc resection but the need for new treatment strategies. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;80:2032-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin YT, Hsu PK, Hsu HS, et al. En bloc resection for lung cancer with chest wall invasion. J Chin Med Assoc 2006;69:157-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Voltolini L, Rapicetta C, Luzzi L, et al. Lung cancer with chest wall involvement: predictive factors of long-term survival after surgical resection. Lung Cancer 2006;52:359-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee CY, Byun CS, Lee JG, et al. The prognostic factors of resected non-small cell lung cancer with chest wall invasion. World J Surg Oncol 2012;10:9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lanuti M. Surgical Management of Lung Cancer Involving the Chest Wall. Thorac Surg Clin 2017;27:195-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiappetta M, Nachira D, Congedo M, et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Chest Wall Involvement: Integrated Treatment or Surgery Alone? Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;67:299-305. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coleman FP. Primary Carcinoma of the Lung, with Invasion of the Ribs: Pneumonectomy and Simultaneous Block Resection of the Chest Wall. Ann Surg 1947;126:156-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tahiri M, Khereba M, Thiffault V, et al. Preoperative assessment of chest wall invasion in non-small cell lung cancer using surgeon-performed ultrasound. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:984-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Padovani B, Mouroux J, Seksik L, et al. Chest wall invasion by bronchogenic carcinoma: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology 1993;187:33-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burnard RJ, Martini N, Beattie EJ Jr. The value of resection in tumors involving the chest wall. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1974;68:530-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazzella A, Loi M, Mansuet-Lupo A, et al. Clinical Characteristics, Molecular Phenotyping, and Management of Isolated Adrenal Metastases From Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2019;20:405-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loi M, Mazzella A, Mansuet-Lupo A, et al. Synchronous Oligometastatic Lung Cancer Deserves a Dedicated Management. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:1053-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rusch VW, Giroux DJ, Kraut MJ, et al. Induction chemoradiation and surgical resection for superior sulcus non-small-cell lung carcinomas: long-term results of Southwest Oncology Group Trial 9416 (Intergroup Trial 0160). J Clin Oncol 2007;25:313-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi K, Yokoi K, Niwa HCentral Japan Lung Study Group, et al. A prospective, multi-institutional phase II study of induction chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery in patients with non-small cell lung cancer involving the chest wall (CJLSG0801). Lung Cancer 2017;104:79-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen D, Wang H, Song X, et al. Preoperative radiation may improve the outcomes of resectable IIIA/N2 non-small-cell lung cancer patients: A propensity score matching-based analysis from surveillance, epidemiology, and end resultsdatabase. Cancer Med 2018;7:4354-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah SS, Goldstraw P. Combined pulmonary and thoracic wall resection for stage III lung cancer. Thorax 1995;50:782-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trastek VF, Pairolero PC, Piehler JM, et al. En bloc (non-chest wall) resection for bronchogenic carcinoma with parietal fixation. Factors affecting survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1984;87:352-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao Y, Wang W, Liang H, et al. The Optimal Treatment for Stage IIIA-N2 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Network Meta-Analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:1866-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yildizeli B, Dartevelle PG, Fadel E, et al. Results of primary surgery with T4 non-small cell lung cancer during a 25-year period in a single center: the benefit is worth the risk. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:1065-75; discussion 1074-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yabuki H, Sakurada A, Eba S, et al. Chest wall/parietal pleural invasions worsen prognosis in T4 non-small cell lung cancer patients after resection. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;67:788-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Mazzella A, Loi M, Alifano M. Prognostic factors of resected lung cancer with chest wall involvement. Curr Chall Thorac Surg 2020;2:6.